As the SEZ concept evolves in Cambodia, a variety of zones have emerged, each with differing characteristics and aims.

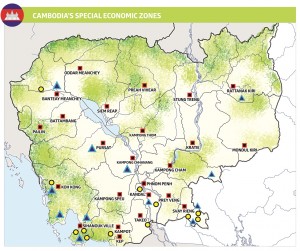

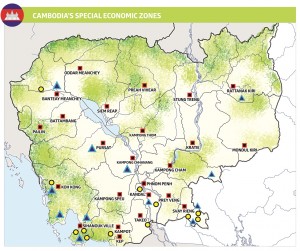

In 2005, after special economic zones (SEZs) were formally introduced in Cambodia through the Sub Decree, Svay Reing’s Manhattan SEZ became the first to began construction the same year. The Sihanoukville SEZ remains Cambodia’s largest with over 1,000 hectares in the area. The $320 million development is said to be capable of hosting 300 factories, offering about 80,000 jobs. As the SEZ concept evolves in Cambodia, a variety of zones have emerged, each with differing characteristics and aims. Currently, around 30 approved SEZs in Cambodia have been authorized by the Cambodia Special Economic Zone Board (CSEZB), which operates under the umbrella of the Council for the Development of Cambodia (CDC). However, while many organizations have obtained SEZ licenses, there is a limited number of SEZs actually operating.

“Overall, an SEZ is a safe place for FDI because the conditions are found to be stable, safe and have less inherent investment and direct operational risk as opposed to locating outside of an SEZ,” said Charles Esterhoy, COO of Phnom Penh Special Economic Zone (PPSEZ).

[caption id="attachment_77479" align="aligncenter" width="300"]

Vireak Mai, Phnom Penh Post[/caption]

SEZs are generally able to save foreign investors from investing extra funds in land development, infrastructure, security and ongoing maintenance.

With a Qualified Investment Project (QIP) license, SEZ tenants will receive tax exemptions on production materials and equipment depending on whether they are in an export or domestic industry. Set period Profit tax exemptions are also available. SEZs can also offer up to 50 years of renewable leases to foreign investors, often allowing them to develop, subdivide or sublease the property. Meanwhile, Cambodian companies can purchase the land outright for development. While property prices in the Phnom Penh CBD and other developing industrial areas are heating up, prices at SEZs generally only see increases based on the costs of operations and the growth plans of that specific SEZ. Comparing prices across SEZs within Cambodia is, therefore, difficult - as each location is unique in what it provides investors and its overall business model. Cambodia currently has some of the highest costs of shipping and slowest freight speeds in the ASEAN region. Efficient import and export of materials and goods into/out of Special Economic zones is, therefore, a vital aspect of their operations for prospective FDI. One such example has been the recent implementation of the ASYCUDA system at PPSEZ, according to Esterhoy, which allows “brokers to process shipments on-line and with much more efficiency.”

Oknha Sear Rithy, board of director for Kerry Worldbridge Logistics Ltd., likewise stressed the need to provide efficient logistic solutions in order to increase FDI in Cambodia. The Kerry Worldbridge Special Economic Zone (KWB SEZ), which opened in Dangkao last week, will be able to provide huge regional reach and efficiency in terms of supply-chain logistics, as the zone draws on Hong Kong-listed Kerry Logistics Network Limited’s vast experience in this field, inside and outside of Cambodia.

[caption id="attachment_77480" align="aligncenter" width="300"]

Vireak Mai, Phnom Penh Post[/caption]

Cambodia also has some of the highest electricity prices in the region.

This means, SEZs focus on reducing costs of electricity within the zone and guaranteeing its consistency, two factors especially important for manufacturers relocating to Cambodia. PPSEZ have partnered with Colben Energy to provide efficient electrical power distribution and stable backup power inside PPSEZ for this reason.

Meanwhile, Oknha Sear Rithy said that KWB SEZ is currently speaking with renewable energy providers regarding plans to bring green energy solutions to the newly- bonded industrial zone. These energy solutions are potentially cheaper than the Cambodian grid can currently offer, and provide for FDI conscious of their environmental footprint.

SEZs are assisting in the diversification of Cambodian export industries and have a close relationship with the Government - but are fully backed by private capital. This makes the application of new and innovative industrial policies particularly easy in SEZs, many acting as testing zones for wider policy initiatives.

As per the 2005 Sub Decree that first instated SEZs in Cambodia, all Cambodian SEZs must employ a majority local work force. Although foreign managers, technicians and experts may be hired, the foreign staff should not exceed 10% of the total workforce. Zone developers often work with the Ministry of Labour to conduct vocational training to promote new skills and knowledge throughout the workforce.

Potential investors in the semi-high tech manufacturing sector often worry that they may face a skills-gap when they move into the Cambodian labour market, one which is still principally engaged in lower-skilled manufacturing sectors such as garments and agriculture. However, SEZs are increasingly offering integrated vocational training facilities within their SEZs, supported by the Government, to ensure their staff can meet the demands of new and higher-skilled industrial developments being brought to the country through FDI. “These sectors,” sais Esterhoy, “create new opportunities, new skills and illustrate the potential of the Cambodian work force.”

Both Esterhoy and Oknha Sear Rithy are seeing a consistent stream of interest from many specialized and semi-high tech manufacturing sectors who are seeking not only a stable manufacturing environment but also a stable business environment. Cambodian SEZs can apparently offer this.

In 2005, after special economic zones (SEZs) were formally introduced in Cambodia through the Sub Decree, Svay Reing’s Manhattan SEZ became the first to began construction the same year. The Sihanoukville SEZ remains Cambodia’s largest with over 1,000 hectares in the area. The $320 million development is said to be capable of hosting 300 factories, offering about 80,000 jobs. As the SEZ concept evolves in Cambodia, a variety of zones have emerged, each with differing characteristics and aims. Currently, around 30 approved SEZs in Cambodia have been authorized by the Cambodia Special Economic Zone Board (CSEZB), which operates under the umbrella of the Council for the Development of Cambodia (CDC). However, while many organizations have obtained SEZ licenses, there is a limited number of SEZs actually operating.

“Overall, an SEZ is a safe place for FDI because the conditions are found to be stable, safe and have less inherent investment and direct operational risk as opposed to locating outside of an SEZ,” said Charles Esterhoy, COO of Phnom Penh Special Economic Zone (PPSEZ).

[caption id="attachment_77479" align="aligncenter" width="300"]

In 2005, after special economic zones (SEZs) were formally introduced in Cambodia through the Sub Decree, Svay Reing’s Manhattan SEZ became the first to began construction the same year. The Sihanoukville SEZ remains Cambodia’s largest with over 1,000 hectares in the area. The $320 million development is said to be capable of hosting 300 factories, offering about 80,000 jobs. As the SEZ concept evolves in Cambodia, a variety of zones have emerged, each with differing characteristics and aims. Currently, around 30 approved SEZs in Cambodia have been authorized by the Cambodia Special Economic Zone Board (CSEZB), which operates under the umbrella of the Council for the Development of Cambodia (CDC). However, while many organizations have obtained SEZ licenses, there is a limited number of SEZs actually operating.

“Overall, an SEZ is a safe place for FDI because the conditions are found to be stable, safe and have less inherent investment and direct operational risk as opposed to locating outside of an SEZ,” said Charles Esterhoy, COO of Phnom Penh Special Economic Zone (PPSEZ).

[caption id="attachment_77479" align="aligncenter" width="300"] Vireak Mai, Phnom Penh Post[/caption]

SEZs are generally able to save foreign investors from investing extra funds in land development, infrastructure, security and ongoing maintenance.

With a Qualified Investment Project (QIP) license, SEZ tenants will receive tax exemptions on production materials and equipment depending on whether they are in an export or domestic industry. Set period Profit tax exemptions are also available. SEZs can also offer up to 50 years of renewable leases to foreign investors, often allowing them to develop, subdivide or sublease the property. Meanwhile, Cambodian companies can purchase the land outright for development. While property prices in the Phnom Penh CBD and other developing industrial areas are heating up, prices at SEZs generally only see increases based on the costs of operations and the growth plans of that specific SEZ. Comparing prices across SEZs within Cambodia is, therefore, difficult - as each location is unique in what it provides investors and its overall business model. Cambodia currently has some of the highest costs of shipping and slowest freight speeds in the ASEAN region. Efficient import and export of materials and goods into/out of Special Economic zones is, therefore, a vital aspect of their operations for prospective FDI. One such example has been the recent implementation of the ASYCUDA system at PPSEZ, according to Esterhoy, which allows “brokers to process shipments on-line and with much more efficiency.”

Oknha Sear Rithy, board of director for Kerry Worldbridge Logistics Ltd., likewise stressed the need to provide efficient logistic solutions in order to increase FDI in Cambodia. The Kerry Worldbridge Special Economic Zone (KWB SEZ), which opened in Dangkao last week, will be able to provide huge regional reach and efficiency in terms of supply-chain logistics, as the zone draws on Hong Kong-listed Kerry Logistics Network Limited’s vast experience in this field, inside and outside of Cambodia.

[caption id="attachment_77480" align="aligncenter" width="300"]

Vireak Mai, Phnom Penh Post[/caption]

SEZs are generally able to save foreign investors from investing extra funds in land development, infrastructure, security and ongoing maintenance.

With a Qualified Investment Project (QIP) license, SEZ tenants will receive tax exemptions on production materials and equipment depending on whether they are in an export or domestic industry. Set period Profit tax exemptions are also available. SEZs can also offer up to 50 years of renewable leases to foreign investors, often allowing them to develop, subdivide or sublease the property. Meanwhile, Cambodian companies can purchase the land outright for development. While property prices in the Phnom Penh CBD and other developing industrial areas are heating up, prices at SEZs generally only see increases based on the costs of operations and the growth plans of that specific SEZ. Comparing prices across SEZs within Cambodia is, therefore, difficult - as each location is unique in what it provides investors and its overall business model. Cambodia currently has some of the highest costs of shipping and slowest freight speeds in the ASEAN region. Efficient import and export of materials and goods into/out of Special Economic zones is, therefore, a vital aspect of their operations for prospective FDI. One such example has been the recent implementation of the ASYCUDA system at PPSEZ, according to Esterhoy, which allows “brokers to process shipments on-line and with much more efficiency.”

Oknha Sear Rithy, board of director for Kerry Worldbridge Logistics Ltd., likewise stressed the need to provide efficient logistic solutions in order to increase FDI in Cambodia. The Kerry Worldbridge Special Economic Zone (KWB SEZ), which opened in Dangkao last week, will be able to provide huge regional reach and efficiency in terms of supply-chain logistics, as the zone draws on Hong Kong-listed Kerry Logistics Network Limited’s vast experience in this field, inside and outside of Cambodia.

[caption id="attachment_77480" align="aligncenter" width="300"] Vireak Mai, Phnom Penh Post[/caption]

Cambodia also has some of the highest electricity prices in the region.

This means, SEZs focus on reducing costs of electricity within the zone and guaranteeing its consistency, two factors especially important for manufacturers relocating to Cambodia. PPSEZ have partnered with Colben Energy to provide efficient electrical power distribution and stable backup power inside PPSEZ for this reason.

Meanwhile, Oknha Sear Rithy said that KWB SEZ is currently speaking with renewable energy providers regarding plans to bring green energy solutions to the newly- bonded industrial zone. These energy solutions are potentially cheaper than the Cambodian grid can currently offer, and provide for FDI conscious of their environmental footprint.

SEZs are assisting in the diversification of Cambodian export industries and have a close relationship with the Government - but are fully backed by private capital. This makes the application of new and innovative industrial policies particularly easy in SEZs, many acting as testing zones for wider policy initiatives.

As per the 2005 Sub Decree that first instated SEZs in Cambodia, all Cambodian SEZs must employ a majority local work force. Although foreign managers, technicians and experts may be hired, the foreign staff should not exceed 10% of the total workforce. Zone developers often work with the Ministry of Labour to conduct vocational training to promote new skills and knowledge throughout the workforce.

Potential investors in the semi-high tech manufacturing sector often worry that they may face a skills-gap when they move into the Cambodian labour market, one which is still principally engaged in lower-skilled manufacturing sectors such as garments and agriculture. However, SEZs are increasingly offering integrated vocational training facilities within their SEZs, supported by the Government, to ensure their staff can meet the demands of new and higher-skilled industrial developments being brought to the country through FDI. “These sectors,” sais Esterhoy, “create new opportunities, new skills and illustrate the potential of the Cambodian work force.”

Both Esterhoy and Oknha Sear Rithy are seeing a consistent stream of interest from many specialized and semi-high tech manufacturing sectors who are seeking not only a stable manufacturing environment but also a stable business environment. Cambodian SEZs can apparently offer this.

Vireak Mai, Phnom Penh Post[/caption]

Cambodia also has some of the highest electricity prices in the region.

This means, SEZs focus on reducing costs of electricity within the zone and guaranteeing its consistency, two factors especially important for manufacturers relocating to Cambodia. PPSEZ have partnered with Colben Energy to provide efficient electrical power distribution and stable backup power inside PPSEZ for this reason.

Meanwhile, Oknha Sear Rithy said that KWB SEZ is currently speaking with renewable energy providers regarding plans to bring green energy solutions to the newly- bonded industrial zone. These energy solutions are potentially cheaper than the Cambodian grid can currently offer, and provide for FDI conscious of their environmental footprint.

SEZs are assisting in the diversification of Cambodian export industries and have a close relationship with the Government - but are fully backed by private capital. This makes the application of new and innovative industrial policies particularly easy in SEZs, many acting as testing zones for wider policy initiatives.

As per the 2005 Sub Decree that first instated SEZs in Cambodia, all Cambodian SEZs must employ a majority local work force. Although foreign managers, technicians and experts may be hired, the foreign staff should not exceed 10% of the total workforce. Zone developers often work with the Ministry of Labour to conduct vocational training to promote new skills and knowledge throughout the workforce.

Potential investors in the semi-high tech manufacturing sector often worry that they may face a skills-gap when they move into the Cambodian labour market, one which is still principally engaged in lower-skilled manufacturing sectors such as garments and agriculture. However, SEZs are increasingly offering integrated vocational training facilities within their SEZs, supported by the Government, to ensure their staff can meet the demands of new and higher-skilled industrial developments being brought to the country through FDI. “These sectors,” sais Esterhoy, “create new opportunities, new skills and illustrate the potential of the Cambodian work force.”

Both Esterhoy and Oknha Sear Rithy are seeing a consistent stream of interest from many specialized and semi-high tech manufacturing sectors who are seeking not only a stable manufacturing environment but also a stable business environment. Cambodian SEZs can apparently offer this.

Comments